Creating a Chai like assertion library using proxies

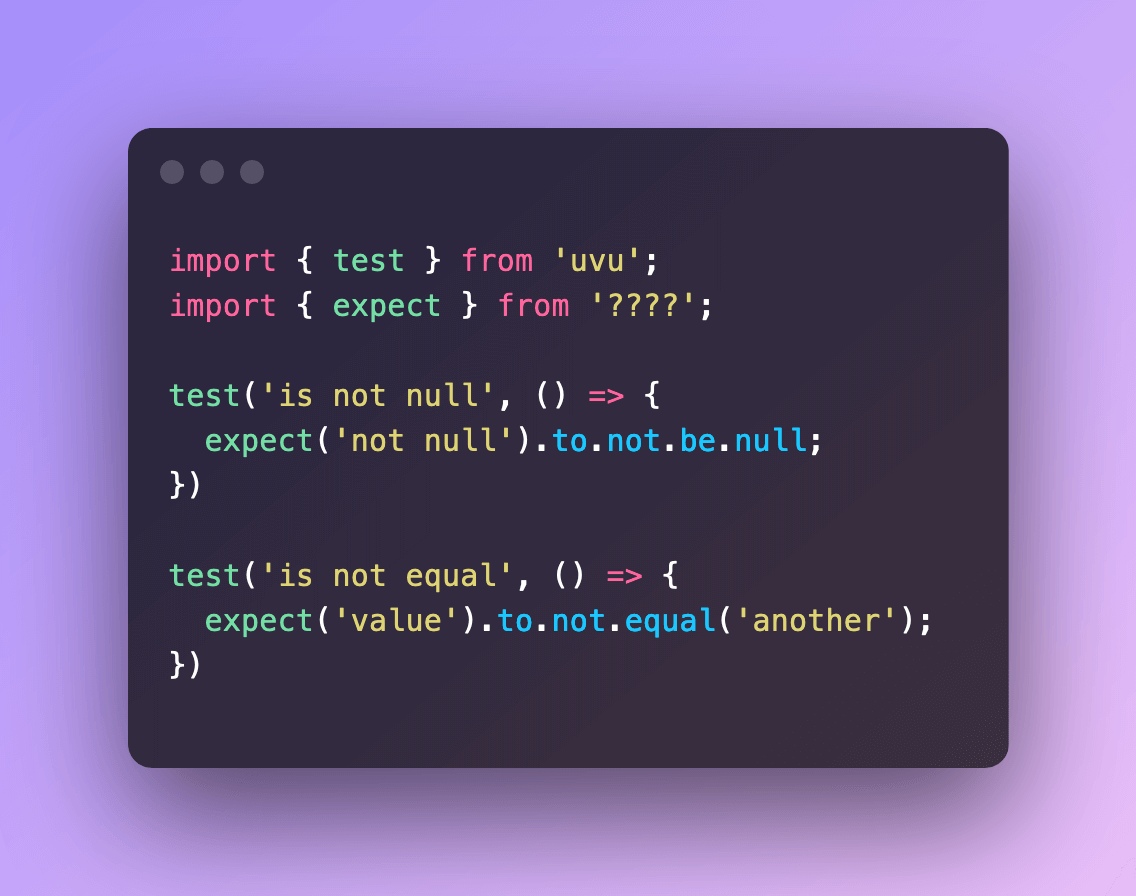

Showcasing how I made a fun side-project to be used with uvu

For the past few weeks I’ve taken the (arguably pointless) work of migrating Felte from using Jest to uvu. This is a really tedious work by itself, but one of details that would have made this work even more tedious is that Jest prefers assertions to the style of expect(…).toBe* while uvu gives you freedom to choose any assertion library, although there’s an official uvu/assert module that comes with assertions to the style of assert.is(value, expected).

While this is fine and I could have perfectly moved all my tests to use said assertion style, I like the descriptive way Jest tests look like. As a quick way to maintain certain similarity I reached for ChaiJS, an assertion library that is mainly used with mocha. Chai offers expect like assertions that can arguably be more descriptive than Jest’s. Instead of writing expect(…).toBe(true), you’d write expect(…).to.be.true. For the most part I managed to do a search and replace for this.

This setup works really good! But there’s some minor details: The assertion errors thrown by Chai are slightly different than those expected by uvu., so sometimes I’d get messages or extra details that are not so relevant to the test itself. Another issue is that I’d receive diffs comparing undefined to undefined when an assertion failed. As a proper developer with too much free time, I went ahead and decided to experiment with writing my own assertion library built on top of uvu’s assertions that I called uvu-expect. Here’s more or less how I did it.

The “expect” function

The main thing our assertion library needs is an expect function that should receive the value you’re planning to validate.

export function expect(value) {

// run your validations here

}

If we wanted to keep a similar API to Jest, this could return an object with functions.

export function expect(value) {

return {

toBe(expected) {

if (expected !== value) {

throw new Error('Expected values to be strictly equal');

}

},

};

}

But I actually really enjoyed Chai’s syntax. So I decided to use proxies to achieve something similar. We could start by allowing to chain arbitrary words after our expect call. I decided not to restrict the possible “chain” words to simplify development.

Proxy is a JavaScript feature that allows you to "wrap" an object in order to intercept and modify its functionality. In our case we will use it to modify the behaviour when accessing our object's properties.

export function expect(value) {

const proxy = new Proxy(

// The target we are adding the proxy on. For now it's empty.

{},

{

get() {

// Any property access returns the proxy once again.

return proxy;

},

}

);

return proxy;

}

expect().this.does.nothing.but.also.does.not.crash;

Next we will allow for any of these chain words to be functions.

export function expect(value) {

const proxy = new Proxy(

{},

{

get(_, outerProp) {

// Instead of returning the initial proxy, we return

// a new proxy that wraps a function.

return new Proxy(() => proxy, {

get(_, innerProp) {

// If the function does not get called, and a property gets

// accessed directly, we access the same property

// from our original proxy.

return proxy[innerProp];

},

});

},

}

);

return proxy;

}

expect().this.does.nothing().but.also.does.not.crash();

With this we already got the base for our syntax. We now need to be able to add some meaning to certain properties. For example, we might want to make expect(…).to.be.null to check whether a value is null or not.

Adding meaning to our properties

We could perfectly check the name of the property being accessed and use that to run validations. For example, if we wanted to add a validation for checking if a value is null:

// For brevity, we're not going to use the code that handles functions.

// Only property access

export function expect(value) {

const proxy = new Proxy(

{},

{

get(_, prop) {

// `prop` is the name of the propery being

// accessed.

switch (prop) {

case 'null':

if (value !== null) {

throw new Error('Expected value to be null');

}

break;

}

return proxy;

},

}

);

return proxy;

}

expect(null).to.be.null;

try {

expect('not null').to.be.null;

} catch (err) {

console.log(err.message); // => "Expected value to be null"

}

This can make our expect function hard to maintain, and adding more properties would not be so trivial. In order to make this more maintainable (and extensible) we’re going to handle this a bit differently.

Defining properties

Instead of proxying an empty object, we will proxy an object that contains the properties we want to have meaning.

const properties = {

// ...

};

export function expect(value) {

const proxy = new Proxy(properties, {

get(target, outerProp) {

// `target` is our `properties` object

console.log(target);

return new Proxy(() => proxy, {

get(_, innerProp) {

return proxy[innerProp];

},

});

},

});

return proxy;

}

I decided to define each property as an object that contains two functions: onAccess to be executed on property access, and onCall to be executed when calling the property as a function. For example, our property for null could look like:

const isNull = {

onAccess(actual) {

if (actual !== null) {

throw new Error('Expected value to be null');

}

},

};

We can also define a property to check if two values are strictly equal:

const isEqual = {

onCall(actual, expected) {

if (actual !== expected) {

throw new Error('Expected values to be strictly equal');

}

},

};

Then we can modify our expect function to call them when they’re accessed:

// We add the previously defined properties to

// our `properties` object

const properties = {

null: isNull,

equal: isEqual,

};

export function expect(value) {

const proxy = new Proxy(properties, {

get(target, outerProp) {

const property = target[outerProp];

// We execute the `onAccess` handler when one is found

property?.onAccess?.(value);

return new Proxy(

(...args) => {

// We execute the `onCall` handler when one is found

property?.onCall?.(value, ...args);

return proxy;

},

{

get(_, innerProp) {

return proxy[innerProp];

},

}

);

},

});

return proxy;

}

expect(null).to.be.null;

expect('a').to.equal('a');

We suddenly have a really basic assertion library! And it can be easily extended by adding properties to our properties object!

There’s one thing we’re still not able to do with our current implementation: negate assertions. We need a way to modify the behaviour of future assertions.

Negating assertions

In order to be able to achieve this, we need a way to communicate to our properties that the current assertions is being negated. For this we’re going to change a bit how we define our properties. Instead of expecting the actual value being validated as first argument, we’re going to receive a context object that will contain our actual value and a new negated property that will be a boolean indicating if the assertion is being negated. Our new properties for equal and null will then look like this:

const isNull = {

onAccess(context) {

if (!context.negated && context.actual !== null) {

throw new Error('Expected value to be null');

}

if (context.negated && context.actual === null) {

throw new Error('Expected value not to be null');

}

},

};

const isEqual = {

onCall(context, expected) {

if (!context.negated && context.actual !== expected) {

throw new Error('Expected values to be strictly equal');

}

if (context.negated && context.actual === expected) {

throw new Error('Expected values not to be strictly equal');

}

},

};

And we can add a new property to negate our assertions:

const isNot = {

onAccess(context) {

// We set `negated` to true so future assertions

// will have knowledge of it.

context.negated = true;

},

};

Then our expect function will call each handler with a context object instead of the actual value:

const properties = {

null: isNull,

equal: isEqual,

not: isNot,

};

export function expect(value) {

// Our context object

const context = {

actual: value,

negated: false,

};

const proxy = new Proxy(properties, {

get(target, outerProp) {

const property = target[outerProp];

property?.onAccess?.(context);

return new Proxy(

(...args) => {

property?.onCall?.(context, ...args);

return proxy;

},

{

get(_, innerProp) {

return proxy[innerProp];

},

}

);

},

});

return proxy;

}

expect('a').to.not.equal('b');

This technique can be used to communicate more details about our assertions to future assertions.

Do not throw normal Errors

To make examples simpler, we throw normal errors (throw new Error(…)). Since this is to be used with a test runner, it’d be better to throw something like Node’s built-in AssertionError or, in the case of uvu, its own Assertion error. These would give way more information when assertions fail. And it can be picked by Node or test runners to show prettier messages and diffs!

Conclusion

This is a simplified explanation of how I made uvu-expect. uvu-expect has way more features and validations such as:

.resolvesand.rejectsto assert on promises- Possibility to create plugins for it using an

extendfunction. This is how I also created a plugin for it called uvu-expect-dom which offers similar validations to@testing-library/jest-dom. - Assertions on mock functions (compatible with sinonjs and tinyspy).

I aimed for it to have at least the features I used of Jest’s expect. You can read more about its features on its README! I documented everything about it there. Even how to create your own plugins for it.

It was a really fun side-project to build and explain. And it’s been working really well with our tests on Felte.